When AI Infrastructure Meets Margin Mastery - My essay on Q3'25 earnings of the S&P500

An Earnings Season That Defied Sceptics — And Exposed the Market's Widening Fault Lines

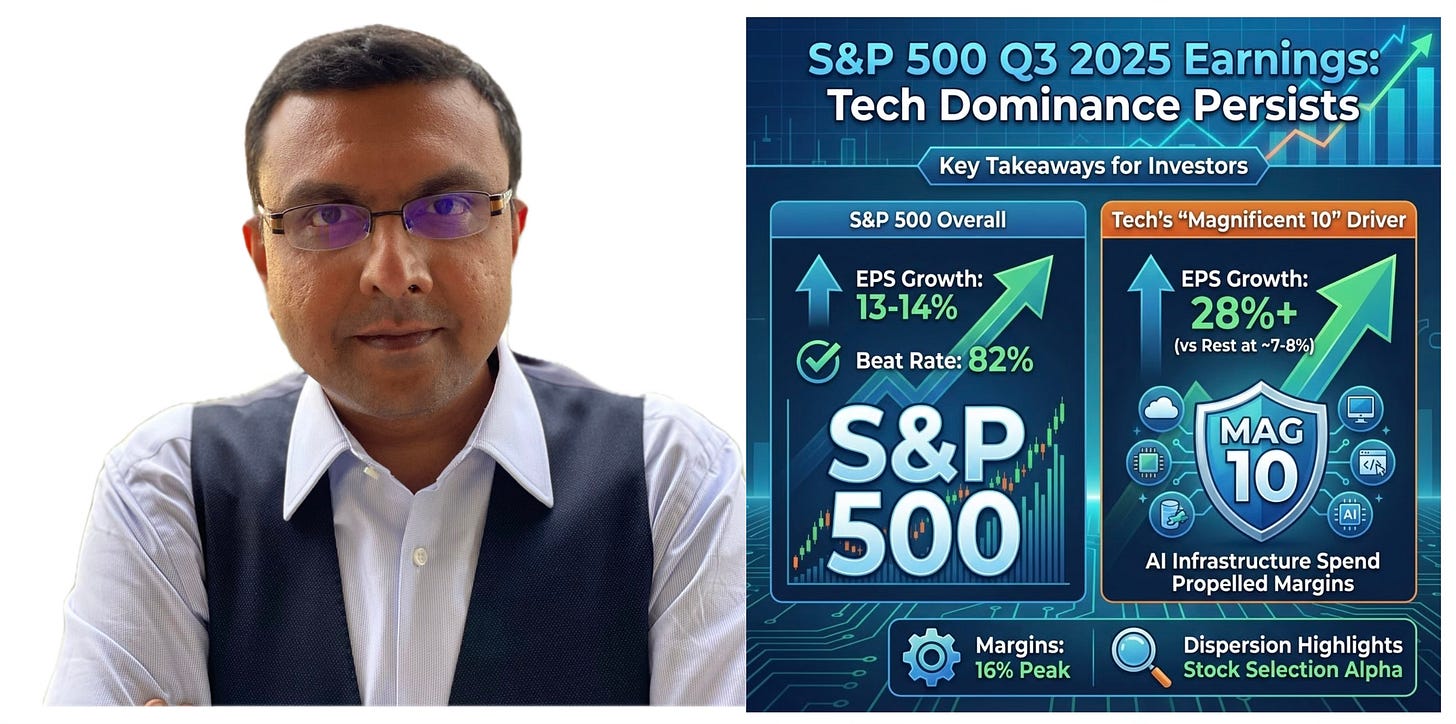

Q3 2025 will be remembered for one thing: American corporate earnings just shattered expectations in a way that few seasoned investors anticipated. Whilst investors fretted over tariffs, artificial intelligence bubbles, and a cooling labour market, Corporate America simply got on with the business of printing profits. The S&P 500 delivered 13 to 14 per cent earnings per share growth, marking the fourth consecutive quarter of double-digit expansion. More remarkably still, the index achieved this feat despite absorbing average tariffs exceeding 11 per cent — a development that confounded virtually every Wall Street forecast made in January.

Yet beneath this headline victory lies a far more complex and unsettling reality.

The earnings gains were not evenly distributed.

They were dominated overwhelmingly by a handful of mega-cap technology stocks pursuing artificial intelligence infrastructure at an almost religious fervour. This concentration has created a fundamental divergence in the market: the Magnificent 10 (and the broader cohort of technology mega-caps) are operating in an entirely different economic universe than the remainder of the S&P 500’s 490 constituents. Understanding this split is essential for any investor seeking to navigate 2026 with conviction.

The Headline Numbers: Better Than Anyone Dared Expect

Let us begin with the headline earnings data, because the numbers are simply extraordinary. The S&P 500’s aggregate earnings per share grew by 13 to 14% year-over-year in Q3 2025, well ahead of the 7% that consensus expected when the quarter began on 30 September. This was the fourth straight quarter of double-digit EPS growth— a rarity in modern market cycles. The earnings beat rate was equally impressive: 78 to 85% of companies exceeded analyst expectations on EPS, a figure that the Goldman Sachs research team recently noted was exceeded only during the post-Covid reopening period of 2020-2021.

Profit margins continued their relentless ascent. The S&P 500’s net profit margin reached 13.1 to 13.6% in Q3 2025 — the highest level recorded since at least 2009. This represented the seventh consecutive quarter of expanding margins, a development that speaks volumes about corporate pricing power and operational discipline in an inflationary environment. Yet what makes this achievement truly remarkable is the context: margins expanded from Q2 to Q3 despite companies absorbing average tariffs exceeding 11 per cent, a feat that prompted the chief equity strategist at LPL Financial to declare: “Few expected that in this policy environment.”

Revenue growth, meanwhile, came in at 8.4 per cent year-over-year, a respectable figure in absolute terms but one that reveals the hidden architecture supporting earnings growth.

The disparity between revenue growth (8.4 per cent) and earnings growth (13.4 per cent) tells the story: margin expansion, not top-line dynamism, is driving the profit narrative.

This distinction matters profoundly for investors assessing sustainability and valuation risk.

The Magnificent 8 Problem: Earnings Concentration in an Extreme Form

If the headline story is impressive, the subheading is alarming.

The “Great 8” mega-cap technology stocks

NVDA 0.00%↑ , AMZN 0.00%↑ GOOGL 0.00%↑ META 0.00%↑ MSFT 0.00%↑ TSLA 0.00%↑ AVGO 0.00%↑ AAPL 0.00%↑

delivered earnings per share growth of 17.6 per cent year-over-year (or 28.7 per cent excluding Meta’s one-time tax charge). Their revenue growth reached 17.5 per cent, roughly triple the pace of companies outside this cohort.

Meanwhile, the S&P 500 excluding these eight stocks managed EPS growth of just 12.1 per cent and revenue growth of a mere 5.3 per cent.

The gap is not subtle. It is a chasm.

The divergence becomes still more pronounced when examining consensus estimate revisions. Since the start of 2025, the “Great 8” have seen their full-year EPS consensus estimates raised by 4.6 per cent. The remainder of the S&P 500? Their 2025 consensus EPS estimates have been cutby 3.4 per cent. In other words, analysts began 2025 expecting broad-based profit growth across corporate America. By November 2025, they were essentially saying:

“The gains are coming from eight stocks. Everything else is facing headwinds we did not anticipate.”

This concentration is reflected in capital expenditure patterns. In Q3 2025 alone, the Great 8 deployed $113.4 billion in capital spending, representing 75 per cent year-over-year growth and the strongest quarterly growth rate of 2025. Full-year 2025 capex for these mega-cap technology firms is now tracking toward $405 billion, representing 62 per cent year-over-year growth. When Morgan Stanley forecast $300 billion in Big Tech capex for 2025, they were already well below where companies have actually landed.

Where is this money going? Almost exclusively into AI infrastructure. Amazon has guided toward approximately $100 billion in capex for 2025, with executives noting that “the vast majority” targets AWS and AI infrastructure. Microsoft disclosed roughly $80 billion, with more than half destined for U.S. data centres. Alphabet signalled $75 billion, whilst Meta outlined $60 to $65 billion before later upward revisions. These figures dwarf historical tech capex cycles and speak to a level of conviction about AI’s commercial potential that corporate boards are willing to stake their capital (quite literally hundreds of billions of it) upon.

The capital discipline is being validated by earnings results. Nvidia’s Q3 revenue reached $35.08 billion, up 94 per cent year-over-year, with earnings per share of $0.78 on a GAAP basis (up 111 per cent year-over-year). The company’s gross margin remained robust at 75 per cent, indicating that the AI chip market has not descended into a commodity pricing environment despite accelerating supply. Microsoft reported Azure revenue growth of 40 per cent, driven squarely by AI and cloud infrastructure demand. Alphabet’s Google Cloud division grew at 34 per cent, powered explicitly by AI enterprise demand. Meta’s reality labs business— ostensibly focused on metaverse hardware but increasingly an AI infrastructure play — surged 74 per cent, driven by strong AI hardware demand.

The Magnificent 8 Fractures: Even Giants Show Strain

Yet here is where the story becomes genuinely interesting: even within the Magnificent 8 (or Magnificent 7, depending on one’s preferred terminology), performance diverged sharply. Tesla, nominally part of this elite cohort, delivered Q3 results that told a different story entirely.

Tesla posted $28.1 billion in Q3 revenue, up 12 per cent year-over-year, but this headline obscures a fundamental deterioration in profitability. Operating income fell 40 per cent year-over-year to $1.6 billion, translating to an operating margin of just 5.8 per cent (versus the company’s historical 10-12 per cent baseline). Net income plunged 37 per cent to $1.37 billion despite record deliveries. The culprits were familiar: vehicle price cuts eroding gross margins (which fell from 19.8 per cent to 18 per cent), operating costs rising 50 per cent year-over-year (driven by AI and R&D investments), and a collapse in regulatory credit revenue (down to $417 million from $739 million a year earlier as EV tax credits expired).

Tesla’s underperformance reflects a fundamental divergence within the Magnificent cohort.

The mega-cap technology companies aggressively raising capital expenditure and AI investment — Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Nvidia — are capturing the value created by AI infrastructure adoption. Tesla, by contrast, is a capex-intensive business competing in an increasingly competitive automotive market whilst simultaneously building out energy infrastructure and AI capabilities. The company finds itself caught between growth investing (which is depressing margins) and a maturing electric vehicle market (which is seeing intensifying competition and tariff pressures).

This fracture within the elite speaks to a broader truth: AI adoption is not benefiting all mega-caps equally. The companies positioned as the “picks and shovels” of the AI boom — those providing chips, cloud infrastructure, or software platforms — are capturing disproportionate value. The companies competing in consumer-facing or capital-intensive businesses are facing margin pressure.

The Rest of the Market: Breadth Without Depth

Turning to the remainder of the S&P 500, the picture is decidedly mixed. The broad equity market is benefiting from the capital cycle created by mega-cap technology investment, but the gains are highly selective.

Technology and Information Services:

Excluding the mega-cap leaders, the broader tech sector still achieved 27-40% growth, with 98% of companies beating revenue estimates. However, within this aggregated figure lay dramatic dispersion. Semiconductor and software companies benefiting from AI capex are thriving. Traditional software and services companies — those not providing AI infrastructure — are struggling. BlackRock’s recent analysis noted that “within the IT sector alone, there is a 305 per cent difference between top and bottom performers” — a gap so wide as to render sectoral analysis almost meaningless.

Financials:

The financial sector delivered 23 to 25% earnings growth with a 90% beat rate, driven by healthy credit conditions, elevated loan volumes, and deregulation tailwinds boosting mergers and acquisitions activity. This has been one of the few genuine breadth winners in 2025, though valuations remain elevated on expectations of continued deregulation and rate stability.

Utilities:

Perhaps the surprise story of 2025 earnings season has been utilities, a sector that traditionally languishes in the doldrums of earnings growth. Utilities delivered 14% earnings growth, driven almost entirely by data centre power demand. Exelon, the parent of Baltimore Gas & Electric, reported Q3 earnings that beat Wall Street estimates, with executives noting a 12% rise in data centre customer demand in the quarter alone. The utility’s pipeline had grown to 19GW of committed data centre load — enough power to supply 14M homes. Similar dynamics are playing out across utilities with geographic proximity to AI data centre buildout. This is the classic “picks and shovels” thesis manifesting in the real economy: as mega-cap tech companies accelerate infrastructure capex, their supporting industries reap disproportionate benefits.

Industrials:

The industrial sector achieved 20% earnings growth, though the distribution was bifurcated. Cyclically exposed industrial companies — particularly those supplying cooling systems, power infrastructure, and components for data centre construction — reported surge orders. Traditional cyclical industrials (transportation, basic manufacturing) showed improvement but lagged the data centre beneficiaries. The sector’s strong performance year-to-date (evident in strong stock price gains) now incorporates expectations of continued good news.

Energy:

The energy sector was a disappointment, with earnings growth effectively flat at 0.3 per cent despite elevated crude oil prices earlier in the year. XOM 0.00%↑ reported third-quarter earnings of $7.5B on record Guyana and Permian output, but the sector as a whole failed to participate in the broader earnings strength. The weakness reflects both commodity price dynamics and the reality that energy is becoming a cyclical afterthought in an AI-focused investment cycle.

Consumer Staples:

The weakest performer was consumer staples, with earnings growth at just 0.8%. Despite holding up well on pricing (79% of staples companies still mentioned tariffs on earnings calls, the highest of any sector), consumer staples companies face a structurally challenged environment of private label competition and consumer bifurcation. The “stressed lower-income consumer” remains under pressure, whilst mid- and higher-income consumers demonstrate resilience.

The Tariff Paradox: How Companies Absorbed $11% Levies and Still Expanded Margins

One of the most intriguing aspects of Q3 earnings was the seemingly impossible feat of margin expansion whilst absorbing average tariffs exceeding 11%. Consensus wisdom in early 2025 forecast that tariffs would squeeze profits, potentially devastatingly so.

That did not happen. Instead, the S&P 500’s profit margins expanded from 12.9% in Q2 to 13.6% in Q3, a quarter in which tariff burdens were most acute.

How did companies accomplish this?

Several mechanisms appear to be at work.

First, companies aggressively passed tariff costs through to consumers. The fact that revenue growth substantially exceeded earnings expectations (after accounting for expected margin compression) suggests successful pricing power.

Second, companies cut costs elsewhere — including labour costs.

Third, some companies pre-ordered inventory in anticipation of tariffs, smoothing the impact across quarters.

Finally, companies operating in high-margin businesses (particularly technology and financial services) saw their profitability weighted earnings gains so significantly that margin-compressed cyclical businesses became statistically immaterial to the aggregate figure.

The implication is clear: American corporations proved far more nimble and resilient than consensus expected. The “tariff tantrum” of early 2025 now looks like a tempest in a teacup from an earnings perspective, though the ultimate consumer impact remains uncertain.

The AI Infrastructure Thesis: Fundamentals, Not Bubble Dynamics

The elephant in the room is the question that dominated investor conversations in late October and November 2025:

Is the artificial intelligence buildout a genuine structural investment opportunity, or is it a bubble wherein companies are deploying capital in pursuit of competitive positioning rather than rational expected returns?

The Q3 earnings season provides compelling evidence for the former thesis, though it does not definitively rule out the latter.

Consider the fundamentals. The AI boom is not concentrated among a handful of companies making speculative bets. Instead, it is spread across the entire cloud and infrastructure value chain. META 0.00%↑ is raising capex guidance to $65B (later revised upward) explicitly to build data centre capacity for AI inference workloads. AMZN 0.00%↑ is deploying roughly $100B toward AI infrastructure. MSFT 0.00%↑ is committing $80B. These are not venture-backed startups gambling on a thesis. These are multinational corporations with fiduciary duties to shareholders deploying unprecedented capital in pursuit of profitable AI services.

The fact that these companies are simultaneously reporting robust profitability, expanding margins, and accelerating capital spending suggests that they are experiencing genuine demand for AI services. If the buildout were merely competitive positioning divorced from actual customer willingness to pay, we would expect to see margin compression, declining return on incremental capital, and weakening guidance. Instead, we see the opposite: expanding margins (even in IT), strong pricing power, and upward guidance revisions.

McKinsey’s forecast of x3.5 growth in AI data centre gigawatts between 2025 and 2030, at an estimated cost of $5.5T (at the midpoint), provides a framework for understanding the scale of this opportunity. If accurate, this represents the largest infrastructure buildout cycle of the 21st century — larger than broadband expansion, larger than mobile infrastructure, certainly larger than the 2000s real estate bubble.

Importantly, BlackRock’s recent analysis found that equity returns in 2025 have been driven overwhelmingly by earnings growth rather than multiple expansion. The firm found that “return of tech and some other AI-exposed sectors has been driven more by earnings than multiple expansion,” with the contribution to returns from earnings being “even greater among the AI-powered tech leaders.” In other words, the market has not valued these companies on hope and speculation; it has valued them on the basis of actual earnings delivering on the AI thesis.

This does not mean risk is absent.

Capital deployment risk exists — the possibility that companies spend $500 billion on data centre buildout only to find that demand disappoints and return on capital is inadequate.

Regulatory risk exists, particularly around export controls and antitrust scrutiny. Competitive dynamics could intensify, eroding the pricing power that has enabled margin expansion. But the thesis that the AI buildout is a rational corporate response to genuine market opportunity — rather than mere bubble dynamics — appears well-supported by Q3 earnings data.

The Divergence Within Sectors: Alpha Awaits the Disciplined

One of the most striking features of Q3 earnings was the extraordinary dispersion within sectors. I noted earlier the 305% performance gap between top and bottom performers in the IT sector alone. Similar dynamics played out across healthcare, industrials, and utilities.

This has been the consistent message from sophisticated asset managers throughout 2025:

The market has moved beyond cyclical and sectoral themes into idiosyncratic, company-specific dynamics.

Vertical spreadsheets — mapping companies by industry classification — are increasingly useless. What matters is whether a company is positioned to benefit from AI capex acceleration (in which case it thrives), whether it faces margin compression from competitive dynamics or tariffs (in which case it struggles), and whether management has demonstrated disciplined capital allocation (in which case guidance revisions tend to be positive rather than negative).

This environment is, paradoxically, both challenging and opportunity-rich. It is challenging because the old playbooks (sector rotation, style rotation, market breadth) are less reliable. It is opportunity-rich because it rewards the fundamental, bottom-up security analysis that was supposed to be the foundation of institutional investing but has been crowded out in recent years by quantitative and thematic approaches.

Consumer Bifurcation: The Fault Line Beneath the Surface

Beneath the headline earnings strength lies a concerning structural divergence in consumer health.

The mid- and higher-income consumer continues to demonstrate resilience. Visa, Mastercard, and major banks all reported robust consumer spending metrics.

Higher-income households benefiting from capital gains and employment are maintaining consumption levels.

The lower-income consumer, by contrast, is visibly under stress. Consumer staples earnings growth at 0.8 per cent (versus double-digit growth in most other sectors) speaks to a consumer at or near its margin.

The bifurcation between private-label and name brands, between discount retailers and premium retailers, has become a defining feature of consumer earnings discussions.

Looking ahead, this fault line could become critical. New tax cuts scheduled to take effect in 2026 could provide support to lower-income consumers, potentially sustaining consumption. Alternatively, if the labour market weakens sufficiently to generate meaningful job losses, consumer spending could deteriorate. The Supreme Court case concerning the legality of Trump’s tariffs — if decided unfavourably — could allow tariff costs to permeate further into consumer prices, further pressuring lower-income households.

Two Key Takeaways for All Investors

First: The earnings growth is real, but it is concentrated.

The S&P 500 has delivered genuine 13-14% earnings growth in Q3 2025. This is not artificial, not driven by multiple expansion or accounting gimmicks. It reflects real profit growth across corporate America. However, this growth is not evenly distributed. Mega-cap technology companies investing in AI infrastructure are capturing disproportionate value. Traditional cyclical businesses are facing margin pressure. Utilities are thriving. Energy is struggling. The key investment implication is clear: broad-based market buying is not justified by earnings growth. Instead, disciplined bottom-up stock selection within sectors is essential.

Second: AI infrastructure investment is fundamentally driven, not speculative.

The hundred-plus billion dollars that mega-cap technology companies are deploying toward data centre capacity, GPU procurement, and AI software development appears to be justified by actual customer demand and profit creation. This does not mean valuations are reasonable or that all companies will earn adequate returns on this capital. It does mean that the investment thesis is not merely a bubble born of competitive hysteria. The risk is not that the thesis is wrong; it is that companies collectively overbuild, that returns on capital prove inadequate, or that regulatory barriers emerge.

Looking Ahead: 2026 Outlook

For 2026, the trajectory is likely to depend on several critical variables.

Will the AI capex cycle sustain at current pace, or will companies moderate spending following what may become apparent as overbuilding?

Will margin expansion continue, or will the year 2026 mark the inflection point where cyclical mean reversion begins?

Will the lower-income consumer finally crack, or will new tax policy support continued resilience?

Will tariff policy stabilise, or will further policy uncertainty create renewed margin pressure?

The Q3 2025 earnings season has provided a strong foundation for 2026 guidance. Year-over-year comparisons will become increasingly difficult (compare 2026 results to 2025’s exceptional 13-14% EPS growth), but the underlying profit drivers — AI infrastructure investment, margin expansion, and industrial resiliency — appear intact.

The market faces not a cliff but rather a gradual deceleration. Earnings growth in 2026 is likely to moderate from current levels, perhaps settling in the 7-10% range, well above historical averages but materially below 2025’s exceptional results. This will likely require multiple compression to justify current valuations — a gradual, patient process rather than a sharp correction.

For investors, the message is clear:

The market is not offering a free lunch in 2026.

Valuations have moved ahead of earnings, and the exceptional profit growth engine of 2025 is unlikely to repeat. However, the underlying corporate fundamentals remain sound, and the AI infrastructure thesis remains intact. Disciplined security selection, a focus on companies demonstrating pricing power and capital discipline, and a willingness to look beyond the Magnificent 7, 8 or 10 — depending on your mood for the day — are the keys to navigating the year ahead.

The Q3 2025 earnings season has written the first chapter of a multi-year technology transition story. The subsequent chapters — how efficiently companies deploy capital, how effectively they monetise AI capabilities, and how markets ultimately value these investments — remain to be written.